Not every dividend tax savings is stripping

Alle pagina's gelinkt aan

It is all over the media: dividend stripping, the biggest tax fraud of all time by white-collar criminals, according to the prosecution. However, preventing dividend tax from becoming a cost is not always fraudulent. For example, by simply selling dividend-generating shares in a timely manner. Selling shares before the dividend date and buying them again shortly thereafter is also allowed, of course. Selling timely, but somehow retaining an interest in the stock and the dividend, that quickly goes wrong.[1]

So certainly not every stock transaction around dividend date is fraudulent.

Although media reports would have you believe otherwise. The much-needed nuances about everything that is called dividend stripping, but is not it in all cases, are in this blog mentioned.

The media hype

The Public Prosecutor’s Office sought the press in June about (at least three) investigations into dividend tax fraud. Denmark and Germany had preceded The Netherlands in investigations into the “fraud of the century”. Billions were allegedly looted from European state coffers. The Netherlands also launched three criminal investigations. Research platform “Follow the Money” had previously posted several reports on the phenomenon, but now that the OM went public, it became national news. ‘It’s bad, really very bad,’ is the tenor.

I don’t rule out that looting has taken place and that billions are involved. But it is wrong to give the impression that everyone is a criminal who manages to prevent dividend tax from entering a state treasury. To lump everything together is unsubtle. Because the dividend tax was reclaimed and received, it is not yet fraud. Just because no dividend tax was ultimately levied on a dividend paid does not mean that dividend stripping has occurred. Dividend stripping is fraud, but just because it walks like a duck and sounds like a duck does not mean it is a duck.

Dividend taxes is basically a withholding tax

Shareholders who receive dividends on their stock holdings are faced with the fact that tax has already been withheld on the dividend received when paid out. Dividend tax has already been withheld upon payment, just as an employee receives his salary net and the payroll tax has already been deducted. Payroll tax is an advance levy on income tax.

After calculating how much tax is due in the annual income tax return, the payroll tax already withheld from the salary is deducted from that payment obligation. If more has already been paid in payroll tax than is due in income tax, you get the excess back. Withheld dividend tax works the same way: dividend tax is (in principle, the exceptions are discussed below) an advance levy on income tax.

In case the shareholder is a corporation, dividend tax is an advance levy on corporate income tax. And if more dividend tax is withheld than you owe in income or corporate tax, you get the excess back.

Income tax example (2023):

An investor has invested €175,000 in shares. On this he receives €8,500 in dividends. From this, 15% dividend tax has already been withheld. Gross therefore € 10,000, tax € 1,500.

In the income tax, no tax is levied on the dividend received, but it is levied on the assumed return on the investments: 6.17% of € 175,000, or € 10,798.

Apart from other income from assets and apart from tax credits and tax-free assets, this investor owes 32% tax in box 3 on the assumed return: €3,455. €1,500 has already been “paid in advance” in the form of dividend tax. He still has to pay an additional €1,955.

If this investment is the only asset, then € 57,000 is exempt, with a tax partner the double. Assuming the latter, he gets (( € 175,000 – € 114,000) x 6.17% x 32% – € 1,500).

So the first impression is, it’s all pretty straightforward. And in purely national cases it is, and dividend tax is ultimately not a cost. Because of all kinds of exemptions in dividend tax (including the participation exemption) and the possibilities to reclaim dividend tax (for example, for pension funds and investment institutions), there is a substantial group of taxpayers who, on balance, pay no dividend tax on dividends received.

But with an investment in foreign shares, or an investment in Dutch shares by someone not resident or established in the Netherlands, set-off suddenly becomes a lot more cumbersome, if not impossible. Because dividend tax is a popular tool for many states to introduce a (withholding) tax on dividends paid by companies in that (source) country. For the recipient this is income, but not in every country dividend tax withheld by the source country is creditable as withholding tax. He therefore first pays dividend tax in the source country and then income tax in his country of residence. Many Dutch treaties have an arrangement to avoid double taxation, but it therefore happens that dividend tax cannot be credited and therefore becomes a final tax. In that case, therefore, an investor loses 15% more of his return than all those others where it is a withholding tax.

‘So what,’ many of the readers may think.

But the difference between having already paid 15% in advance (or not having to pay) and having lost 15% extra is the reason why attempts are made to avoid this difference, often legally, sometimes not: dividend stripping. Not only large corporate investors try to optimize their returns, but often these are precisely pension funds that want to be able to pay out the highest possible pension to private pensioners. The fact is that this creates a market for dividends because a dividend is worth more to some (who can deduct) than to others (who cannot). That market, using the rules for set-off and refund of dividend tax and thus within the legal possibilities, does its work.

In addition, ‘we’ also do not want the choice of which company to invest in to be influenced by this difference. And this is even regulated at European level: Article 63(1) TFEU stipulates that all restrictions on the movement of capital between Member States and between Member States and third countries are prohibited (the principle of freedom of capital).

This principle applied to this matter means that it is not the intention that investments in national companies are favoured over investments in foreign companies, because for the latter investments the dividend withholding tax is a final levy.[2] A trio of European rulings yields that no levy of dividend withholding tax is allowed if the beneficial owner of the dividend is legally or practically not allowed or not able to set off the withholding tax.[3]

This is about the band of unequal treatment. For example: if Dutch pension funds are allowed to reclaim dividend withholding tax, in principle the same applies to foreign pension funds. So, in such a case, dividend tax should be reduced. And not only for dividend payments within the European Union, also in relation to countries outside.[4]

Dividend tax as final tax remains fodder for litigation

Despite these European rules, dividend tax is still a final tax in many cases. Legally or practically. In the legal sense because many proceedings in The Netherlands break down because of “incomparability” with Dutch entities. The comparability with the Fiscal Investment Institution, for example, often (just) fails,[5] and without a comparable entity that is treated better than you, the freedom of capital accomplishes nothing.

In practical terms, reclaiming dividend tax is being made so complicated that many are abandoning it. According to the FD, research shows that 70% of private investors who are entitled to a dividend tax refund fail to apply for it. This may amount to €5 billion a year, according to EU Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni (Economy). Other research indicates that 30% of private investors sold their European equity portfolio because of this tax hurdle.”[6]

Meanwhile, the Tax Chambers of the Breda District Court and the Den Bosch Court are bogged down in proceedings over these obstacles to the free movement of capital. Due to a preliminary question asked by the Court of Den Bosch, proceedings are “parked” for the time being.[7] Much tax evasion amounts to under-declaring to the tax authorities, or wrongly deducting costs. In dividend tax, the issue is different, namely the interpretation of legal texts on exemption or set-off. The frauds take place on the borderline between being entitled or not entitled to exemption/settlement of this tax.

Dividend stripping

A complex of transactions in which shareholders, while retaining the economic interest in their shares, reduce or completely avoid the dividend or other tax burden on distributions on the shares is also known as “dividend stripping” or “dividend washing. The construction in which two legal entities, one in an advantageous position (dividend tax creditable), the other in a disadvantageous position (dividend tax is final tax), trade shares with each other to gain a tax advantage is considered undesirable. Already more than 20 years ago, in July 2002, with retroactive effect to April 27, 2001, an anti-abuse provision to prevent dividend stripping was introduced in both corporate and income tax and dividend withholding tax.[8]

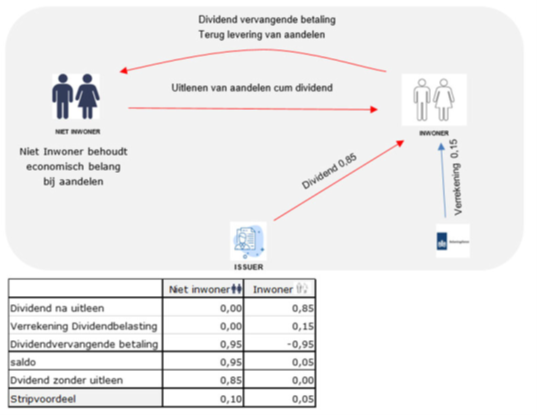

Briefly, those statutory measures mean that a credit or refund of dividend tax is excluded for the person who received the dividend and requests a credit or refund of dividend tax but is not the beneficial owner (UBO) of the dividend. Schematically, dividend stripping (among other things) involves the following situation:[9]

The UBO is not very easy to define. In the legal text, they didn’t even get into it. The most detailed is the commentary on Article 10 of the OECD Model Convention 1992, which has many similarities with the conditions the Supreme Court indicated in its “Market Maker” ruling, which I will come to below. From the statutory measures, it is especially clear what an UBO is not in any case: he who enjoys the proceeds, but in return passes on (part of) the proceeds to a less entitled person who has moreover retained his interest in the shares.

Dividend arbitration: the market maker

Every year the Supreme Court publishes a number of old ‘landmark’ judgments on jurisprudence.nl. One would almost not believe in coincidence, but on March 31, 2023, it came out with the 1994 “Market Maker ruling.”[10] The Supreme Court ruled in that case that the interested company had become the owner of dividend certificates through purchase. it could freely dispose of those dividend certificates after the purchase and, after exchange, of the distributions received. In redeeming the certificates, it did not act as fiduciary or agent. Under these circumstances, according to the Supreme Court, the interested party had to be considered the beneficial owner of the dividends. Van Brunschot annotated the ruling that the state secretary’s position, that the interested party could not be considered the beneficial owner if, for example, he was bound by contractual obligations to pass on the vast majority of the proceeds received to third parties, had virtually no resonance in international doctrine and was now deemed by the Supreme Court to be “airborne.”

Double dip or more

The media are quick to mimic German authorities where dividend tax seems to have been reclaimed twice or even three times. Or dividend tax was reclaimed when no dividend tax was withheld at all. The reports are provided with smooth designations such as ‘çum cum’, ‘cum ex’ or the deployment of ‘REPOs’. To my knowledge, these practices have not occurred in the Netherlands. The Dutch proceedings that I know of are about cases where litigation has taken place to prevent the dividend tax from being a final levy.

If those proceedings are lost, the dividend withholding tax is final levy and, as a rule, the dividend will actually be taxed twice. This is questionable from an international perspective. If the dividend flows to a tax haven, then I have no problem with dividend tax as final tax. But to a country where tax is normally levied on profits?

By the way: in the proceedings I was involved in, the Inland Revenue had not imposed any penalties either, which again emphasizes that this was a tax discussion about the correct interpretation of a legal provision. Nor did the Inland Revenue consider this to be fraud.

Rounds or arbitration?

According to statements from the Prosecutor’s Office, three criminal investigations into dividend stripping are now underway. Because these investigations are still early days, it has not been disclosed what exactly they are about. Since not so many cases are published on rechtspraak.nl, and the topic does not keep the legal world very much off the streets, some estimate can be made.

In a May 12, 2020 ruling, the Amsterdam Court of Appeal, in a departure from the district court, concluded that the interested party in that case was not the UBO. [11]

Around dividend date, lent shares are repeatedly called up for a while. The Court leaves open whether there is dividend stripping or fraus legis (abuse of right), but in any case blocks the dividend tax credit. Whether this case can still be successfully prosecuted criminally is another question. Because of the positive outcome at the court, there could be a pleading position that prevents prosecution. Only in cases where the “pleading” is too much about the “facts” and too little about the “law,” can the prosecution still succeed. Recently, the District Court of the Northern part of The Netherlands ruled that the interested party in those proceedings was not a UBO.[12]

This involved a somewhat more complicated group situation, but where the parties knew each other and knew who they were dealing with. The District Court of The Northern part of The Netherlands refers to this form of cooperation as a “round”.

Such a ’round about’ precludes recognition of the interested party as UBO.

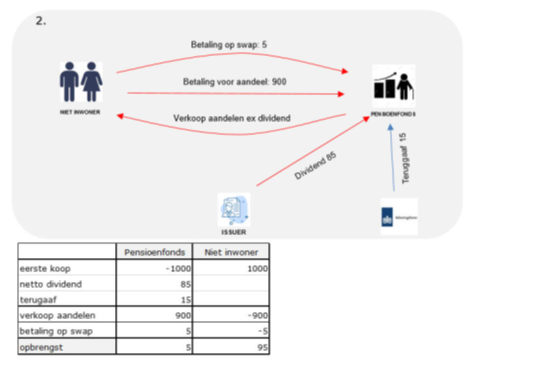

Different in this context, more of a ‘market maker case’, is the Amsterdam Court of Appeal ruling of June 18, 2015.[13] This ruling deals with the subjective corporate tax exemption of a pension fund.

Because of the suspicion of dividend stripping, the accusation is that the pension fund is being abused for stripping, because a pension fund recovers dividend tax due to its corporate tax exempt status.

Schematically, dividend stripping with a pension fund goes in much the same way:[14]

It does not end well for the corporate tax exemption, but on the accusation of abuse and dividend stripping, the Court of Appeal rules that there is no dividend stripping, in part because the interested party does not know the party whose shares are acquired.

On that ignorance, the Court considers the following: (that it) in the context of the (profitability of its) arbitrage transactions, it is also not necessary or relevant to know who its counterparty in the share transactions is. If and to the extent that the buyer of the options and the seller of the shares are in a less favourable (dividend) tax position than the interested party, it is clear that a `spread’ exists on which to arbitrate. If the interested party has written the options and thus determined the selling price of the shares ex-dividend, only the purchase price of the shares cum dividend

In conclusion

Dividend tax is an advance tax on earnings. The main interest for states is to tax those profits themselves, rather than having it accrue to the other state in the form of a profit or income tax. That does not make it okay to avoid that withholding tax, but the desire to avoid double taxation or to be treated the same as so many others is understandable. Moreover, a market is created because dividends are worth less to some than to others. That price difference may be traded. That trade, dividend arbitrage, comes in all shapes and sizes and has been going on for decades.

Since 1994, based on the Supreme Court’s market-maker ruling, it has been clear that a beneficial owner of dividends may reclaim or credit dividend tax. As of 2001, for the first time in the Netherlands, some legal limits were set on who is not considered the beneficial owner and therefore who is not entitled to a refund or credit of dividend tax. Since then, the tax authorities have not been sitting still. Subsequent taxes are regularly levied or reclaimed if the inspector believes that there has been unjustified dividend arbitrage. Until now, this has not been accompanied by fines, because the inspectors also recognized that many refund requests were pleading. There is also a clear line in tax case law: if you are a player in the dividend arbitrage market, you only cross the line of ‘stripping’ if you know the counterparty. If you do not know the counterparty, then you are entitled to a refund or set-off; if you do know the counterparty, then dividend stripping (‘a roundabout’) is involved. So, what is not allowed is clear: move shares for a while and make arrangements to distribute that dividend tax.

So, it is going too far to lump all unwelcome dividend transactions together and label them as fraud when doing so mitigates dividend tax, which would be final tax. But even for the non-tax-permitted cases of dividend arbitrage, if carried out transparently, I wonder whether you should fall over that so hard, given the backgrounds and objectives of dividend tax. The situation is of course different if the tax authorities are deliberately and cunningly deceived.

Sources

[1] Selling, but retaining interest sounds contradictory. This is done, for example, by contractually agreeing redelivery (at predetermined prices). Derivatives are also often used for this purpose, with the same effect.

[2] According to the case law of the Court, measures which are prohibited under Article 63(1) TFEU because they restrict the free movement of capital also extend to those measures which are liable to dissuade non-residents from making investments in a Member State, or which are liable to dissuade residents of that Member State from making investments in other Member States (see in particular judgments of 10 April 2014, Emerging Markets Series of DFA Investment Trust Company, C-190/12, ECLI: EU:C:2014:249, paragraph 39, and November 22, 2018, Sofina e. a., C-575/17, ECLI:EU:C:2018:943, para. 23 and case law cited there).

[3] Where dividends paid to non-resident pension funds bear a heavier tax burden than dividends paid to resident pension funds, there is such less favorable treatment (see, to that effect, Case C-10/14, C-14/14 and C-17/14 Miljoen and Others, ECLI:EU:C:2015:608, paragraph 48). The same applies when dividends paid to resident pension funds are wholly or partially exempted, while dividends paid to non-resident pension funds are subject to final withholding at source (see, to this effect, judgment of November 8, 2012, Commission v. Finland, C-342/10, ECLI:EU:C:2012:688, paragraphs 32 and 33).

[4] ECJ November 13, 2019, British Columbia, ECLI:EU:C:2019:960. British Columbia is a Canadian province, or not a Union. The previous two footnotes are margin numbers 48 and 50 from this judgment.

[5] For an example of the difficult discussion, see A-G Wattel’s conclusion of May 27, 2022, ECLI:NL:PHR:2022:517

[6] FD 20 June 2023, Simpler tax refund saves investors five billion euros according to Brussels

[7] Prejudicial question Hof ‘s-Hertogenbosch December 14, 2022, ECLI:NL:GHSE:2022:4471

[8] Articles 25 (2) and (3) Vpb, 9.2 (2) IB and 4 (4) DB

[9] Source is the ‘Knowledge document Dividend Stripping External’ of the Financial Expertise Center dated 20 August 2021, p. 48

[10] Supreme Court 6 April 1994, ECLI:NL:HR:1994:ZC5639

[11] Amsterdam Court of Appeal May 12, 2020, ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2020:1189

[12] Rechtbank Northern part of The Netherlands 4 July 2023, ECLI:NL:RBNHO:2023:6247

[13] Amsterdam Court of Appeal June 18, 2015, ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2015:3142. The judgment is no longer available for reasons unclear to me, only the judgment and the conclusion PG preceded it.

[14] Source again is the “Knowledge Document Dividend Stripping External” of the Financial Expertise Center dated August 20, 2021, p. 52

Stuur een reactie naar de auteur